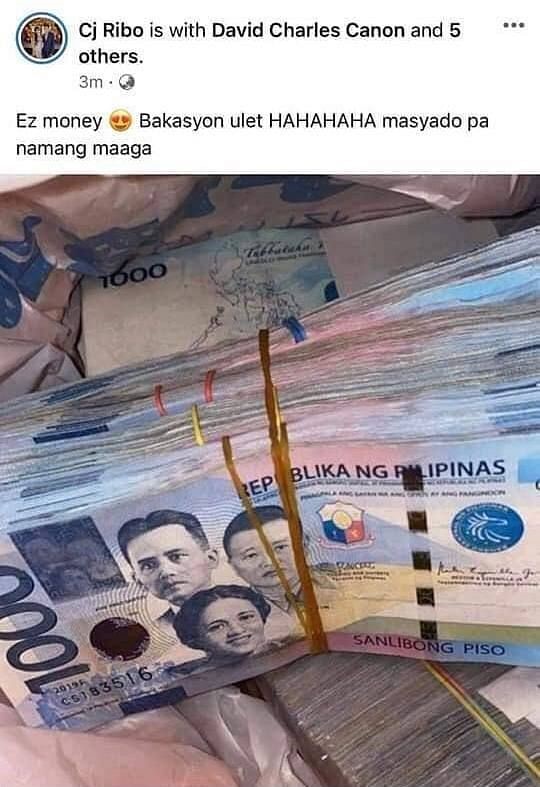

Filipino gamers will remember the infamous social media post in March this year by CJ “Ribo” Ribo.

After his team Bren Esports lost to Onic PH and Nexplay Esports in quick succession in the MPL PH Season 7, Ribo posted a picture of stacks of pesos. The accompanying social media caption read: “Ez Money. Vacation again, HAHAHAHA it’s still too early anyways.”

Was he involved in match-fixing? Some in the MLBB community definitely thought so, and not surprisingly, given how the rising number of high-profile cases in the last decade or so.

Ribo eventually clarified that the money came from a personal business.

“To those saying that we threw the game just for money, fools, we didn’t throw the match, we just lacked practice,” stated Ribo in a subsequent Facebook post.

The controversy over his post and the match-fixing accusations show how the esports world has been shrouded by “322” scandals. The number “322” has become associated with players deliberately throwing away games for money since 2013, when Russian player Aleksey “Solo” Berezin bet against his own team in a major Dota 2 event and won US$322.

There have been a few “322” scandals in the Southeast Asian region. In fact, when Amihan Esports announced Jacko “Jacko” Soriano as part of their MLBB team earlier this year, it was met with some criticism.

You see, Jacko was part of what has been dubbed the “PH 322 scandal of 2014”. At just 15 years old, he was a member of the Mineski Dota squad that threw a match for money, and was banned from participating in Valve events such as Majors and TI. That year, a total of 16 Southeast Asian players were found guilty of match-fixing, including players from Malaysia’s Arrow Gaming.

Sadly, “322” scandals still surface occasionally in the region. This year, Singapore registered its first known case of esports match-fixing, with five Resurgence players banned by Valorant Esports after one of them made S$3,000 worth of illegal bets against his own team. But it is not just a regional phenomenon.

The police are here! And not just in GTA

It is not surprising that esports match-fixing is becoming rife worldwide with the money in it. According to Market Insights, the global eSports Betting market was valued at US$12.67 billion in 2020 and is projected to reach US$20.73 billion by 2027.

Cue a big crackdown. In 2016, in the absence of a regulatory body in the scene, the Esports Integrity Commission (ESIC) was formed by British attorney Ian Smith to unite the esports industry against corruption and to protect the integrity of competitions. It has since roped in tournament operators, national federations and betting organisers such as Betway and GGBet to join the mission against match-fixing.

But it is a huge uphill battle for ESIC. First, it needs to gather the clout of more national federations. Currently, there are only five official supporters listed on its website – Mongolia, Switzerland, New Zealand, Portugal and The Bahamas.

Second, certain quarters have questioned its neutrality, with some saying that the ESIC falsely asserts matches are fixed so betting operators don’t have to pay out winning bets. Such accusations have been rubbished by ESIC Commissioner Smith, who has also called match-fixers “idiots” in the past.

But besides the ESIC, perhaps more law enforcement agencies need to step into the fray to stamp out esports match-fixing. And they don’t come bigger than Interpol. The force’s Match-Fixing Task Force highlighted the protection of esports integrity when it met last year.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in the US has also worked with ESIC to investigate US gamers over match-fixing and illegal betting in Counter-Strike competitions.

Such law enforcement agencies will certainly provide more teeth in dealing with match-fixers. We’re looking not just at bans, but even fines or jail terms.

Ensuring that competitions are clean is crucial to the future of esports. Research director at data firm Ampere Analysis, Piers Harding-Rolls, believes strongly in this.

He told the BBC that esports integrity is “paramount to its commercial potential”.

“Clearly, it’s positive that law enforcement is getting involved in investigating these match-fixing allegations. This is the kind of robust response that is needed to help guide esports into a place where it can be more directly compared with traditional sports and continue its shift towards the mainstream,” he added.